Original version posted February 1, 2013. Updated February 24, 2014.

Disclaimer: I know I can be verbose and ramble on for what seems like ages - so, if you don’t think you can make it through the long diatribe below that introduces the following video, skip ahead, and just watch the video - because it is a video that I think EVERYONE needs to see! On the other hand, if you have a cup of tea/coffee/neurobliss/rootbeer and a few minutes to kill, read on.

From time to time, I get asked why I study LGBTQ psychology, same-sex relationships or, more colloquially: “gay stuff.” When I began graduate school, I never intended on studying “LGBTQ Psychology,” and in fact, I had never heard of such an area of psychology, and wouldn’t for many years. At that time, I just wanted to study relationships, and in fact, relationships research is still the field with which I most closely identify. When I began my research, however, I found myself continually asking “but, does this apply in the same way to same-sex relationships?” More often than not, the answer was that no one had yet conducted a study to find out. Consequently, as I began designing my own studies about intimate relationships, I always made sure that I included same-sex couples. My interests grew from simply how relationships function, to how relationships influence our health, and thus my interests in same-sex couples expanded as well, leading to inquiries about LGBTQ health experiences and minority stress. Over time, I have met more and more individuals who study various aspects of sexuality and LGBTQ psychology and through collaborations, my interests have continued to grow, such that now I would describe myself as a social/health psychologist with primary areas of interest in relationships, health and LGBTQ psychology.

When I began studying same-sex relationships, same-sex marriage was a newly minted phenomenon in Canada, and still a distant dream in the United States. The media in Canada still buzzed with debates about same-sex marriage and whether the Government of Canada would find away to reverse the Supreme Court of Canada’s ruling (which stated that it was against the Charter of Rights and Freedoms to restrict the institution of marriage to only ‘one man and one woman’). Today, Canadians mostly seem to take same-sex marriage in stride, not giving it a great deal of thought or debate, despite the odd article that pops up, reminding us that even in Canada, there are still wrinkles to be ironed out when it comes to the legality of same-sex marriage. Even in the United States it seems as though there is a general sense of momentum that is propelling the country towards legalizing same-sex marriage, and although there is still quite away to go, most reasonably minded individuals (on either side of the debate) seem to be coming to the realization that it is going to happen: someday.

So, when people ask me why I study LGBTQ psychology, at times I am at a loss for words in coming up with an explanation. Perhaps the battle is nearing and end and I’ve launched a career on a dying trend. I think all researchers come to a point where they have stared at their computer screen for a few too many hours, seeing nothing but tiny cells of numbers that, on the surface, appear meaningless. Their overly intimate knowledge of their data and studies can lead to viewing whatever it is that they’re studying as the most boring topic on the face of the planet. Results begin to look like nothing more than common sense and the researcher begins to have difficulty remembering exactly what the original impetus for the study might have been. Despite these feelings that most researchers experience at one point or another (especially when working on dissertations or long, drawn-out studies), in most cases, the research is quite interesting, relevant and meaningful - they’ve just grown too close to still be able to see the big picture. I am certainly not immune to these feelings. There are days where I cannot begin to fathom why I do what I do, where it is going, or even where it has been! Luckily, however, these bouts never seem to last for too long, and eventually, something or someone comes along to jostle me out of my thick fog of doubt and doom.

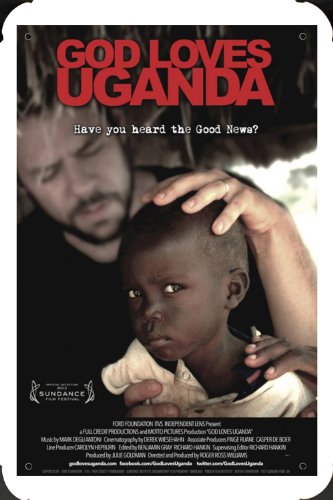

Most recently, one of these ‘phases’ was brought to an abrupt ending by a documentary film that premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. Being new to Salt Lake City, I figured it was an appropriate rite of passage to actually attend a Sundance film in person - but I hadn’t the foggiest clue how to go about selecting which film to see. One afternoon, while I was actually in New Orleans for the SPSP Annual Meeting (suffering from a horrible case of “my research is pointless, it’s so.... how did that guy who looked at my poster put it?? -- oh yea... DUH!”), I was spending some “me” time with CNN, and up on the screen popped Roger Ross Williams, being interviewed about his Sundance film premiere: God Loves Uganda. The news anchor referred to the film as “the most terrifying movie of the year,” and although I hate scary movies, the rest of the preview told me that this was definitely the Sundance film that I wanted to see. I quickly went online and found that there was one showing left with tickets for sale, and luckily for me, it was the one actually in Salt Lake City!

I bought two tickets, and a few

nights later Ashley and I were in line at the Tower Theatre in SLC

waiting to get in to see the film. We got there early, wanting to make

sure that we would get good seats, and so we stood in line for about 45

minutes. Luckily, the major deep freeze had ceased, but it was still a

chilly evening, so Ashley and I were huddled close together in line as

we waited. I looked around and I saw a wide range of people in line,

many of them same-sex couples, and I thought to myself - even here, in

Utah, a state that is not exactly known for its “gay-friendly”

attitudes, same-sex couples were fairing pretty well, holding hands,

snuggling, kissing - basically doing anything to stay warm. Granted, we

were at a Sundance film, and we were at 9th and 9th - a relatively

‘trendy’ area in the state’s most liberal city (a city that has even

made it onto the Advocate.com’s list of gayest cities), but still, for a

Canadian couple used to knowing that the Charter has our back, waiting

in this line made us feel a little bit less far from home. I’m sharing

these minute details of waiting in line not because I’m dead certain

that everyone is just dying to know about ‘the adventures of Karen and

Ashley waiting in line,’ but rather to juxtapose this experience with

the experiences of LGBTQ individuals on the other side of the world that

we were about to witness in Williams’ film.

There are plenty of summaries and reviews of God Loves Uganda circulating on the net already, so I won’t add another one here, but suffice to say, the film unearths what I consider to be utter human depravity and a complete disregard for the lives, rights, and freedoms of other human beings. Worst of all, the crimes against humanity discussed and portrayed in the film are perpetrated in the name of God, and are essentially ‘bought and paid for’ by American Christian Evangelists invading a vulnerable foreign nation to spread a severely warped and distorted version of the “good news of Jesus Christ.”

Central to the film’s purpose is the explication of Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill, potentially set to pass as early as this February (2013). [Update: February 2014 The bill has been passed into law - officially criminalizing Homosexuality in Uganda. The full text of the bill can be read here.] The bill makes homosexuality illegal, punishable by life imprisonment. The bill goes so far as to enact penalties against those who would support LGBT individuals or issues, making it illegal to not report knowledge of an LGBTQ individual. In other words, parents who do not report their LGBTQ children to the authorities could face 7 years in jail. Similar penalties are in place for those who officiate same-sex marriage, counsel LGBTQ individuals or run LGBTQ related businesses.

I wish I had been able to watch the film a few more times, as I felt as though each frame required minutes of processing in order to truly digest everything that was exposed by the film. (You can find local screenings of the film in your area by clicking here. The film will be released on DVD May 19, 2014 - click here to pre-order). In the end, I was left with a multitude of emotions: anger, sadness, disbelief, guilt, gratefulness, shame, helplessness, powerlessness ... to name but a few.

The film also polarized me with respect to my own work. On the one hand, it only exacerbated the feelings of pointlessness and doubt that I was feeling in New Orleans. How can I spend time studying the effects of relationship approval on the health of individuals in same-sex relationships when on the other side of the world a government is debating whether or not to kill individuals who would even attempt to have a same-sex relationship or participate in any form of same-sex sexual behaviour? What is the point of examining a question that becomes so utterly meaningless contrasted against what is happening in Uganda? Furthermore, what research could I EVER do that could even HOPE to make an impact on a situation such as the one in Uganda, where it seems that scientific research means nothing in the face of a diluted and distorted “word of God?”

I stuck with this viewpoint for a few days, overwhelmed by the magnitude of the issues this world still has to face when it comes to human rights, and specifically, the treatment of LGBTQ individuals. Eventually, however, the ‘other hand’ of the story began to show itself, and I felt re-invigorated about my research. Understanding how relationship approval influences the health of individuals in same-sex relationships may do little for what Uganda is currently facing, but that doesn’t mean that it will do nothing at all. When researchers can provide the media, professionals, and society with empirical evidence, attitudes can be changed. If a parent’s approval of their adult child’s same-sex relationship can safeguard that child’s health and well-being, it’s possible that possessing such knowledge might convince someone to change their views on their child’s same-sex relationship. If not that, then perhaps the research will be useful in changing the law and providing evidence for why there should be institutionalized forms of support for same-sex relationships (i.e., marriage), and perhaps as those laws change, there will be a trickle down effect that seeps into the hearts and minds of individual citizens. If this happens, if we (researchers, activists, politicians, experts, ordinary Joes) continue to do our work in improving the lives of LGBTQ individuals that are within our grasp, then perhaps the person we might soon influence will be a Mom in Kansas City who decides she will withhold her donation to the International House of Prayer because she doesn’t agree with their actions in Uganda. It is not lost on me what a long chain of events such an outcome requires, but I choose to see that hurdle as a challenge worth meeting, rather than impassable obstacle.

So, while I have many reasons that I study LGBTQ Psychology, some intentional, some accidental; and while, like many researchers, I wax and wane in my ability to see the bigger picture and where my work fits within it, if you asked me today, “Why do you study LGBTQ Psychology?,” my answer would be this: Because it is an area where my work can make a difference in the lives of others, it is an area where I can examine both the positive and negative aspects of the human experience, and because if people like Bishop Christopher Senyonjo (featured in God Loves Uganda) can have hope for the future of LGBTQ rights in Uganda, then I’m certainly not going to be the one to walk away and say that I have nothing to contribute.

Below you will find an extended Op-Ed Video from the New York Times that gives a good summary of the content portrayed in God Loves Uganda, and below that, you will find the official God Loves Uganda trailer. Please share these videos with your friends and family, and if you are interested in hosting a screening of the film, you can fill out the form found here.

Gospel of Intolerance: New York Times Op-Ed

Official Trailer for God Loves Uganda

Follow:

If you enjoyed this post, consider becoming a KLB Research Patron to help support our research and our ability to disseminate our results in accessible and free formats!