Update: A slightly more "professional" version of this blog entry was published in Relationships Research News from the International Association of Relationships Research. Blair, K.L. (2014). The state of LGBTQ-inclusive research methods in relationship science and how we can do better. Relationship Research News, 13(1), 7-12.

I’ve written about inclusive research practices before, and have placed an emphasis on the importance of including gender and sexual minorities in relationships research. Although psychological research in general has come a long way in being more inclusive with respect to studying topics of relevance to LGBTQ populations, close relationships research still seems to be a bit slow on the uptake. But, to be fair, it can be sometimes difficult to really judge what is currently going on in a field if one only relies on the currently published articles available in scientific journals. After all, not all research gets published, and even when it does get published, it is often years after the initial study was designed. Consequently, a survey of the most recently published close relationships articles might only provide a ‘snapshot’ of the research practices that were prevalent between 2010 and 2013 (or even earlier). Perhaps a better opportunity to get a more current snapshot of the field’s practices is by examining poster presentations at a large conference, such as the Society for Personality and Social Psychology’s Annual Meeting. The advantage of examining poster presentations is that they tend to be reporting more recently conducted research and they provide a sampling of studies that have already been published, those in the process of being published, and those that will never be published (either because they get rejected or because publication just isn’t pursued).

The Close Relationships Poster Session for the SPSP Annual Meeting was held today – appropriately so, given that it is Valentine’s Day! I had a chance to visit 58 of the 71 posters that were listed in the program – I missed one or two, and many others were absent (presumably due to the horrendous East Coast weather that has prevented many from making their annual SPSP pilgrimage).

Results of My Mini-Analysis

Of the 58 posters that I viewed, 45 of them had topics for which the notion of sexual identity would be considered relevant. Only 15.5% of the studies stated that LGBTQ participants were included. Of these, one study was specifically focused on LGBTQ participants, two studies made comparisons based on sexual identity or relationship type, and 5 studies indicated what percentage of their sample was LGBTQ.

Only 15.5% of the studies stated that LGBTQ participants were included.

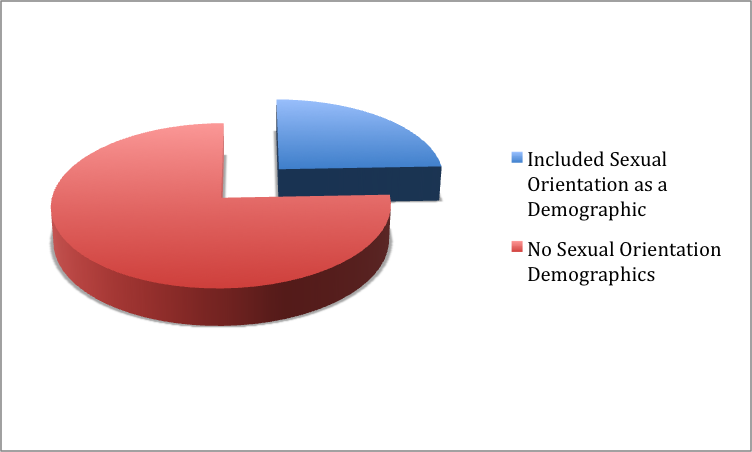

Across the same 45 studies, 24.4% included sexual orientation demographic information while 75.6% provided no information as to the sexual orientation/identities of the participants. 63% of the studies that included sexual orientation information in their sample descriptives were studies that included LGBTQ participants. Only 4 studies indicated that the participants were heterosexual or in mixed-sex relationships (although often termed as opposite-sex relationships) - the rest left the question to our imaginations!

75.6% provided no information as to the sexual orientation/identities of the participants.

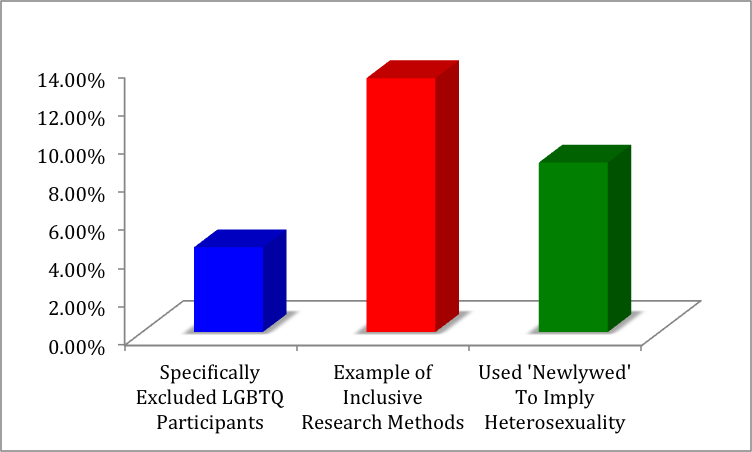

Two studies specifically excluded LGBTQ participants, either as part of the selection criteria for the study or in a post-hoc manner by dropping the data from the analyses. In my previous postings on this subject I have expressed a preference for the latter method, if either is to be used, given that it at least avoids the process of LGBTQ individuals facing explicit rejection from research through signs like “Heterosexual Couples Needed for Research” or exclusion messages such as “we’re sorry, you do not qualify for this study” (after indicating that they are not heterosexual).

Only 13.3%, or 6 studies, qualified as what I would consider ‘inclusive research’ in that the study included participants of multiple sexual orientations and did not exclusively focus on the experiences of a single sexual orientation or group of orientations..

….. or not?

Five studies indicated that they were using newlywed participants, and of these only 1 indicated the sexual identity of the participants (heterosexual), while the others seem to leave this to be implied by the term, ‘newlywed.’

None (zero) of the studies considered the role of gender identity.

One study mentioned that they excluded individuals who did not identify as either male or female. One study indicated that additional data relevant to trans* experiences had been collected, but not yet analyzed.

Overall, I find two troubling conclusions that can be drawn from this information:

- The majority of close relationships research (as represented by this poster session at least) still continues to exclude LGBTQ participants from their studies and to focus on the experiences of those in mixed-sex relationships (which they continue to refer to as opposite-sex relationships). (Okay, maybe I worked in more than one thing there).

- The majority of close relationships research appears to not even see sexual orientation or identity as a relevant demographic worth reporting. Of the 75.6% of the studies that did not mention sexual orientation, we are left to guess who might have been in their sample. Either the researchers themselves do not know who was in the sample because they did not ask, or they know that they excluded LGBTQ participants but have declined to provide this information when presenting their research. While I’m not in favour of excluding LGBTQ participants from the get-go (except for in certain circumstances), I do think that it is at least important to provide this kind of information when presenting research so that it is clear exactly who is in the sample.

The fact that demographic information is important to understanding the context and generalizability of research findings did not appear to be lost on the majority of presenters, who by and large reported many other pieces of demographic information about their samples: ethnicity, nationality, age, gender, relationship status. There were only three posters on which I could find no demographic information whatsoever to describe the sample. So if you, as unnamed researcher X, understand that it is important for your reader to know that your sample was 98% White, 1% Latino, .5% African American and .5% ‘Other’, why does the sexual orientation or identity of your participants seem to be irrelevant? Given that you are studying relationships, it seems that this piece of information could be particularly relevant.

What’s up with the 75.6%?

- They didn’t ask about sexual orientation/identity:

- This could mean that they are assuming everyone is heterosexual, or;

- They are assuming that sexual orientation is irrelevant to their subject of study and that whatever a person’s sexual orientation may be, the study questions and procedures will be appropriate – this scenario could either be very progressive – or very flawed.

- They excluded non heterosexuals before they even made it into the study:

- This issue has been discussed at length here. And here. And here too.

- Creating exclusion perpetuates heteronormativity and day-to-day social exclusion of LGBTQ individuals – and goes against the ethical guidelines laid out by many institutions and agencies. Perhaps researchers' underlying sense of this injustice is what keeps them from presenting this aspect of their method in their presentation?

- There are cases were exclusion is warranted. In these cases, it can go a long way to explicitly state your case. For example, one might say: "We restricted our sample to 20-25 year old heterosexual males given the high cost of using the MRI machine for each participant and wanted to limit the number of confounds in our exploratory pilot study."

- They allowed LGBTQ participants to complete the study, asked them about their sexual identity, but then dropped them from their analyses – and didn’t tell anyone.

- This is better than the “No Gays Allowed” approach to participant recruitment, but the information should still be shared with your readers (as was done by only one poster – XX were dropped from the analysis for sexual orientation and XX were dropped for gender identity). Even still, it is good to provide a rationale as to WHY they were dropped beyond simply stating the demographics of who was dropped. It’s not uncommon to see percentages in the high 90s when researchers outline how many of their participants were White -that’s a whole other issue! – but they also don’t go to the next line and state “5% were dropped due to being African American and 5% were dropped due to being Latino."

- They asked about sexual orientation/identity, but they just didn't include it on their poster.

- This is just a matter of leaving out relevant information. It is possible that they analyzed the sample as a whole, it is possible that they dropped the LGBTQ participants, or it is possible that they compared groups and just didn't report the information. The bottom line is that we just don't know because the information wasn't shared - yet this is important information that researchers do need to share.

Take Home Points:

- It would appear that close relationships researchers are still a long way off from successfully adopting inclusive research methods;

- Try not to exclude LGBTQ participants without a good reason (not sure? click here);

- Include sexual orientation as a demographic – and then report your findings;

- Even if your sample is 100% heterosexual (and I find that VERY hard to believe given the degree of fluidity that has been established among both men and women), you still need to point that out to your readers, along with the reason for why – did it just happen that way? Did you exclude LGBTQs? Did you drop them from the analysis?

- If you’re leaving information about your sample off your poster because you have a nagging feeling that someone will be upset with your methods or that you feel like a jerk for saying you excluded LGBTQ participants…. Maybe you should take that as a hint!

- Not all newlyweds are in mixed-sex relationships. (Shocking, I know.)

- Similar to #6, not all expecting parents are in mixed-sex relationships either! (There goes the bubble!)

So, for now, it would appear, judging based on this sample of recent studies within the field of close relationships, that we still have a ways to go before inclusive research practices concerning sexual and gender identity can be considered the norm.

If you enjoyed this post, consider becoming a KLB Research Patron to help support our research and our ability to disseminate our results in accessible and free formats!